When “work” doesn’t work

I recently gave a talk on vaccine communication, and the most common feedback I got was appreciation for the section on words that confuse people.

I’ve written before how a lot of “misinformation” can more aptly be described as miscommunication — public health saying one thing, and the public hearing something entirely different. These commonly misinterpreted words drive a lot of that confusion.

So here’s the talk for you — my top five words that I’ve seen trip people up when talking about vaccines. The goal isn’t to say you can never use these words again (that would be difficult), but to understand how they can be easily misinterpreted and recognize when it’s happening.

1. “Work”

- Intended medical meaning: Significant reduction in a bad outcome

- Misinterpreted meaning: completely effective in stopping a bad outcome

When scientists or clinicians say a medical treatment (or vaccine) “works,” they mean it reduces (but does not necessarily eliminate) the risk of a bad health outcome. Saying antibiotics “work” does not mean that nobody will die from sepsis ever again.

But many people interpret this word differently — they expect a vaccine that “works” to be one that completely eliminates the possibility of catching the disease. This confusion is partly driven by 1. ambiguity of the word and 2. people’s experience with childhood vaccines (as we’ll see in a second).

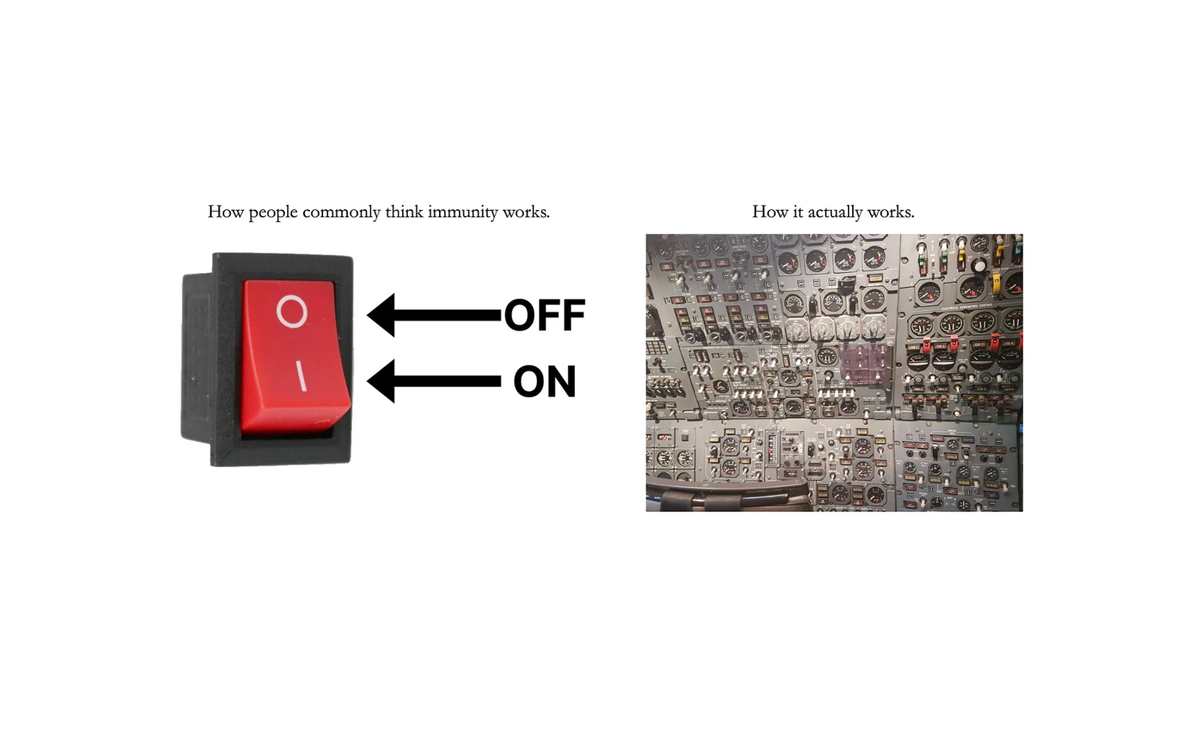

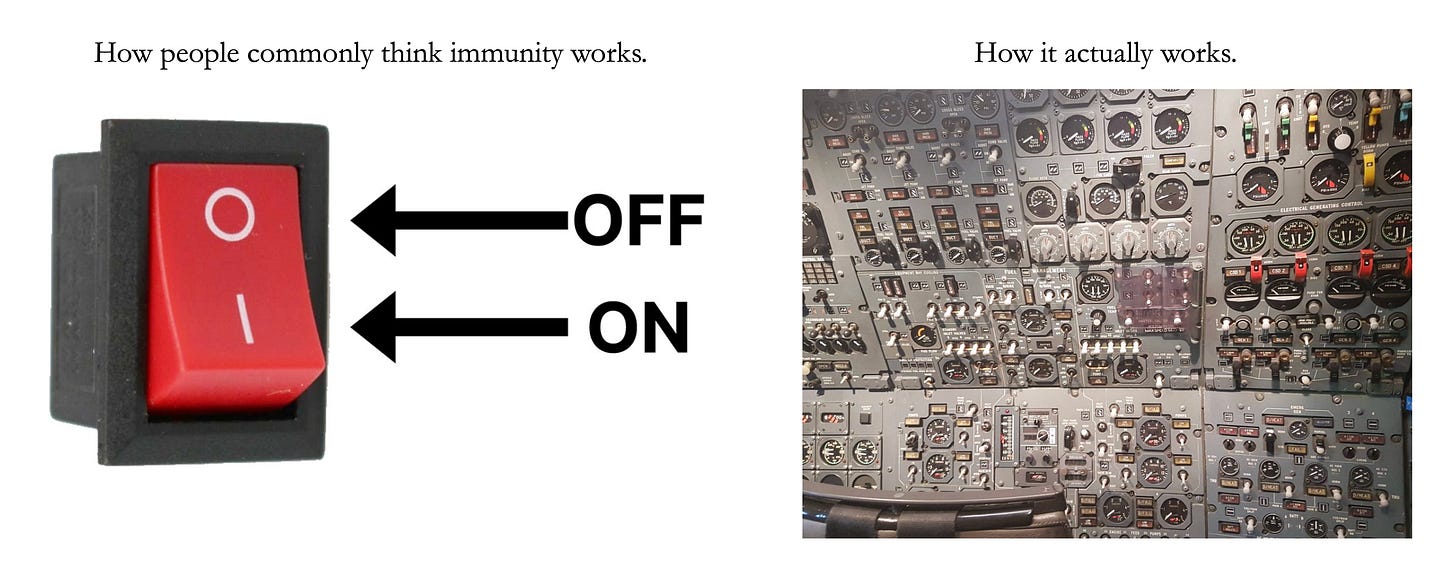

2. “Immunity”

- Intended medical meaning: the state of having immune cells that can recognize and are ready to fight a particular disease (but not a guarantee they will win)

- Misinterpreted meaning: complete protection from a disease (or jail. or zombies.)

In every day language, having “immunity” often means having a golden shield of protection. It’s a yes/no thing — either you are protected or you aren’t. Legal immunity means you can’t be prosecuted (not you are 90% less likely to be prosecuted). In zombie movies, having immunity means the zombies can’t get you — period.

Due to experiences with childhood vaccines, this is how many people believe our immune system works too. When a kid gets vaccinated against polio in the US, their chance of catching polio is vanishingly small — not only because the vaccine is highly effective, but also because the child is unlikely to encounter polio in the first place thanks to herd immunity. But the effect of herd immunity is often overlooked, making vaccine-induced immunity seem basically perfect: if you get vaccinated, you’re not going to catch it. This has led many to believe vaccine-induced immunity is like zombie immunity — it’s all or nothing.

But it’s not. The immune system is one of the most complicated systems in the human body, and the degree of protection it provides is not all or nothing. Both vaccine-induced and disease-induced immunity provide varying degrees of protection — for some vaccines the protection is very strong, and others (like the flu vaccine) it’s more moderate. And some infections induce very little immunity at all. (There are also vaccines prototypes that induce very little immunity, but they don’t make it past being a prototype.)

3. “Prevent”

- Intended medical meaning: Reduce risk of outcome

- Misinterpreted meaning: completely stop outcome

The ambiguity of this word has driven so much of the confusion around vaccines and transmission. Vaccines can prevent (reduced the risk of) transmission, but not prevent (completely stop) transmission. Similarly, car seats prevent (reduce the risk of) childhood deaths, but are not a guarantee they will prevent (completely stop) every childhood death from every car accident ever.

4. “Safe”

- Intended medical meaning: low risk of side effects, benefits outweigh the risks

- Misinterpreted meaning: no risk of any side effects

No medical treatment is 100% without any risk whatsoever. Penicillin is a widely used and generally very well tolerated antibiotic, but it carries the very small risk of anaphylaxis. Blood transfusions save lives and generally don’t cause issues, but carry the rare risk of severe complications. Going to the doctor’s office is generally quite safe, but there is the rare risk of a car accident along the way.

There are very few things in life that are truly 100% risk free, and that is especially true in medicine. Holding that as the standard of what is deemed “safe” is not particularly helpful, because it is a bar that is not met by much of anything.

Instead, the bar for what is safe is set by 1. the likelihood of the bad outcome, and 2. how severe the bad outcome is. When clinicians say something is “safe,” they mean the risk of a severe outcome (like anaphylaxis) is very small.

But I’ve seen this word trip people up so much, I prefer framing this discussion around weighing the risks and benefits of a treatment instead of labeling things as “safe” or “unsafe.” A helpful medical treatment is one where the benefits outweigh the risks.

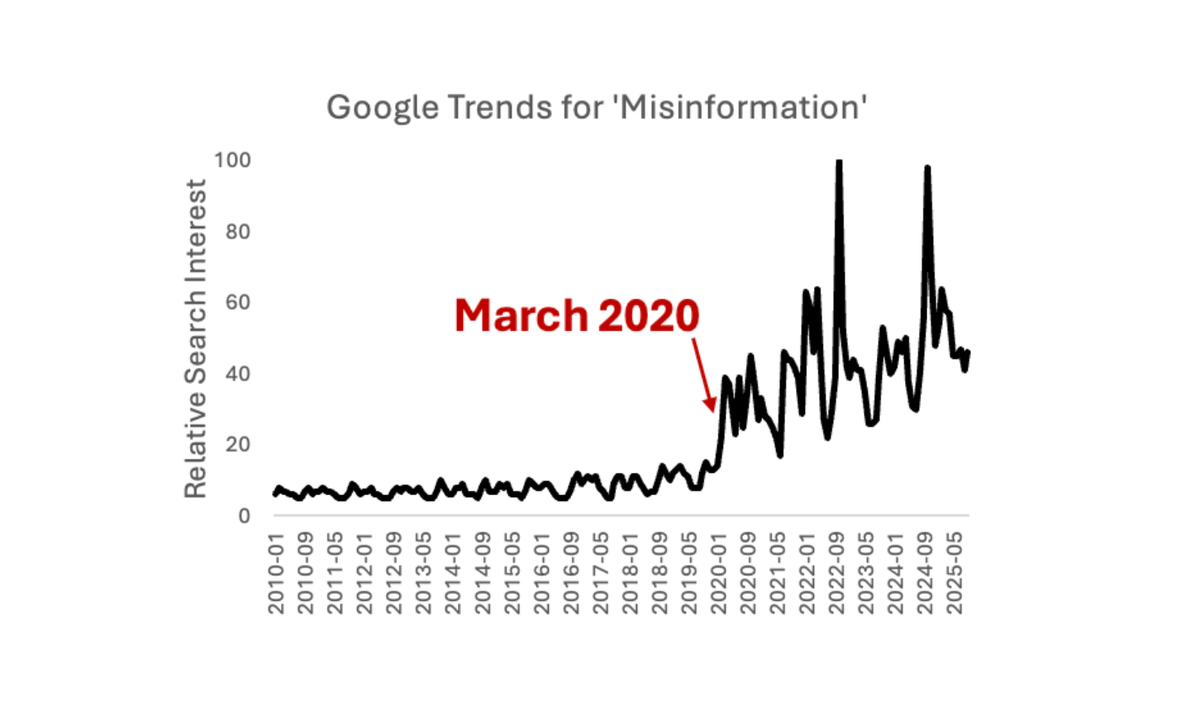

5. “Misinformation”

- Academic meaning: inaccurate information

- Common interpretation: information you’re not allowed to question

I’ve written about this in depth before, but it had to be added to the list. The word ‘misinformation’ has come to mean so many different things to different people that it has largely stopped functioning as a useful word. What’s worse, for many people it carries a sting of accusation and shame that is counterproductive to communicating. Except in academic settings, this one I’d recommend avoiding if possible.

I hope this will help you have more productive conversations about vaccines and realize many vaccine arguments stem from people using the same words to mean entirely different things. Once we can agree on a meaning, it makes communicating a whole lot easier.

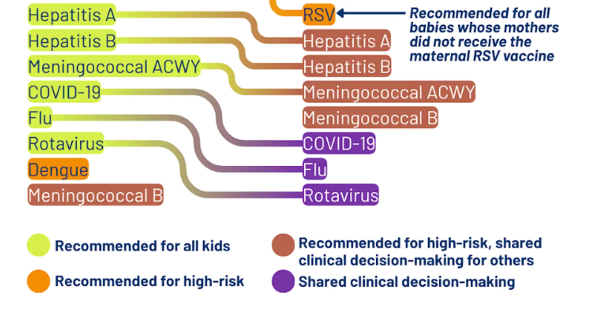

Before you go, I wanted to share a resource created by my friends at The Evidence Collective in anticipation of this week’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) meeting — a thorough document on anticipated concerns and rhetorical tricks that are likely to surface. You can download it for free here!

Kristen Panthagani, MD, PhD, is completing a combined emergency medicine residency and research fellowship focusing on health literacy and communication. In her free time, she is the creator of the medical blog You Can Know Things, available on Substack and youcanknowthings.com. You can also find her on Instagram and Threads. Views expressed belong to KP, not her employer.