What happens when public health says “we're not sure?"

A new study suggests trust may actually increase

One of the most difficult parts of science communication is effectively communicating uncertainty. The scientific method is a powerful tool that over time leads us to the right answer, but it sometimes gets things wrong along the way. When we talk about a scientific fact or new emerging data, where are we in that process? Just how certain are we that it’s actually true?

Communicating uncertainty is not easy. Science communication is always a trade off between simplicity and nuance, and making simple, black and white statements about what science “says” is often a whole lot easier than diving into the messy details. This is especially true online, where short attention spans and an algorithm that judges content by its first three seconds push you towards making bold, simple statements.

And for some, the concern goes further — if scientists and clinicians don’t seem confident in what they say, will people trust them? If they say “here’s what the early data show, but we’re not 100% sure,” is that going to be weaponized against them to say “see, they don’t really know!” It can sure feel that way in the comments section.

But an overly confident, black and white approach to science communication can backfire too. Failing to communicate uncertainty can set up false expectations, leading to disappointment and loss of trust when science later course corrects, as it often does. We saw this frequently during the pandemic (don’t wear masks! actually do! The vaccine is 100% effective against severe disease! Actually it’s not!) and we’re still bearing the consequences of those communication blunders.

So which approach is better — confident and simple, or nuanced with uncertainty on full display? A new study helps answer this question. Published this month by Southwell et al., this study evaluated how communicating uncertainty impacted perceived trustworthiness and understanding of a public health message.

Here’s what they did.

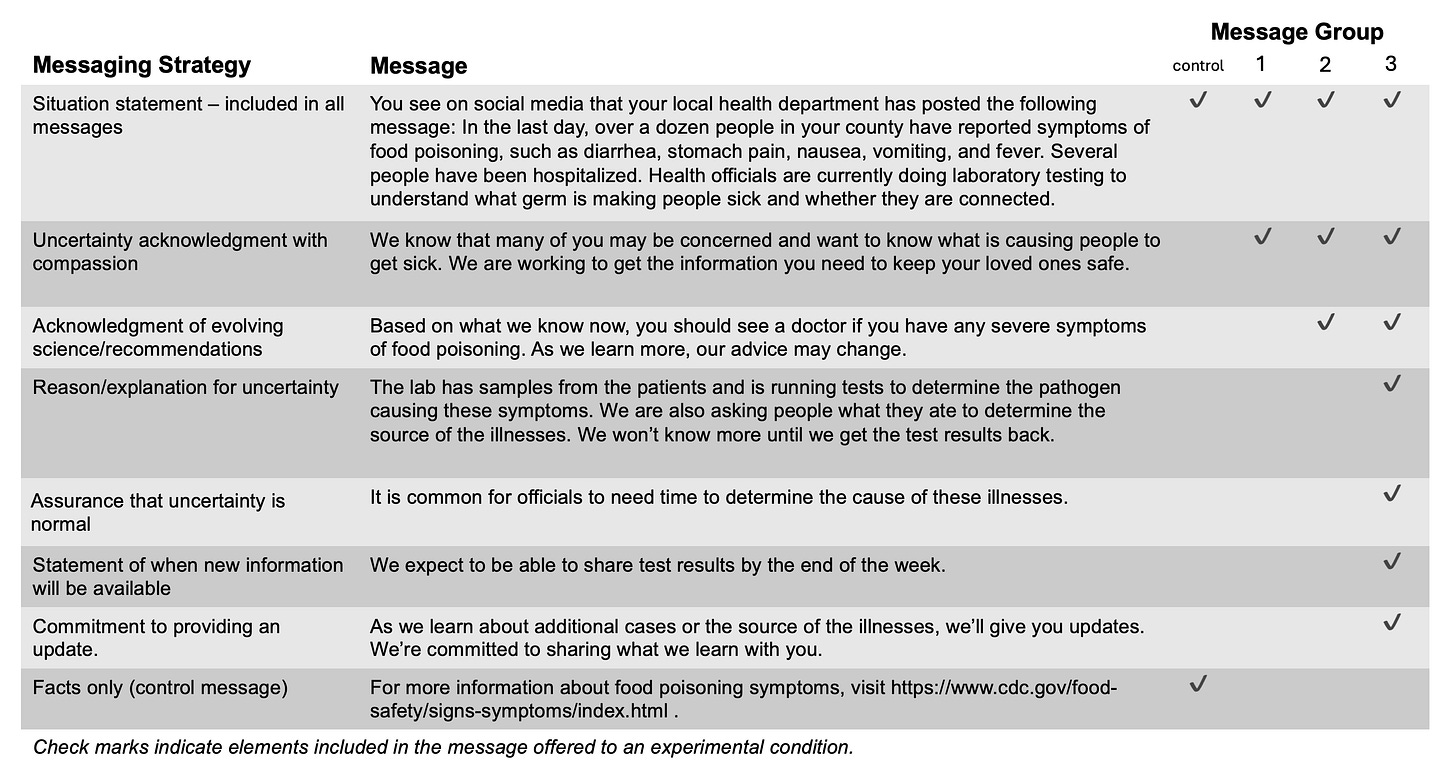

First, they created a hypothetical scenario: a new outbreak of a foodborne illness. They crafted four different messages notifying the public about the outbreak. Some of the messages were “just the facts,” but other messages included varying statements communicating the uncertainties around the situation and next steps to expect (see table). Using a survey of over 4000 people, the researchers measured perceived trustworthiness of the message and perceived understanding of the situation.

Different messages communicated uncertainty in different ways. Group 1 included a simple statement about uncertainty (‘we are working to get the information you need’) as well as compassion (‘we know that many of you may be concerned.’) Group 2 added an acknowledgement that science and recommendations may evolve (‘As we learn more, our advice may change.’) Group 3 included multiple additional statements including assurance that uncertainty is normal, explaining the reasoning for uncertainty, when to expect an update, and an assurance that the update will be provided. The control group contained no acknowledgment of uncertainty and only included information about the outbreak and a link to the CDC website.

What they found

Compared to the “just the facts” control group, all three messages that communicated uncertainty were associated with higher perceived trust and understanding of the message. In other words, when people saw a message that was more than just the facts and a link to the CDC website, they trusted the information more.

The study found that the most detailed uncertainty message (group 3) was associated with higher perceived trustworthiness than the shorter uncertainty messages (groups 1 and 2). This suggests that people want and appreciate the details, and providing them may enhance trust in public health messaging.

Uncertainty wasn’t the only variable that impacted trustworthiness and understanding — lower trust in health institutions and perception that the message was too long were both associated with lower perceived trustworthiness and understanding. So communicating uncertainty isn’t a magic fix if people already distrust public health, but it can still be a step in the right direction.

Is this study right?

It would be a little hypocritical to write this article without addressing the uncertainty around this research study itself — is this study the definitive answer on the subject?

Of course not, no single study ever is. And like every research study, there are limitations (does this survey really reflect the real world where people are going to encounter messages? If people saw that long message on Facebook, would they actually read it or scroll past and miss the message all together?) And uncertainty is only one facet of health communication — empathy, connecting over shared values, understanding the public’s concerns, and finding the right messengers all matter too.

But a single imperfect study can still provide useful information — and this one certainly does. For me, it’s a reminder that people value nuance and honesty about complexity, and that it’s worth the effort to include it, even when social media algorithms punish that choice. As my friend Katelyn Jetelina often says: don’t underestimate the public. They can handle — and want — the messy details.

Kristen Panthagani, MD, PhD, is completing a combined emergency medicine residency and research fellowship focusing on health literacy and communication. In her free time, she is the creator of the medical blog You Can Know Things, available on Substack and youcanknowthings.com. You can also find her on Instagram and Threads. Views expressed belong to KP, not her employer.