Is science inherently political?

It depends on which "science" we're even talking about

Should science stay out of politics—or is science inherently political? When is advocacy appropriate for scientists, and is it even possible to separate the two?

These questions have been debated for years in the world of climate science and resurfaced during the COVID-19 pandemic. The latest round, highlighted in The Atlantic this past weekend, underscores the catch-22 many scientists currently face: sweeping political changes are undermining the infrastructure needed for science to function. Yet when scientists push back against these policy changes that are threatening their jobs, their response is often branded “political.”

The debate: is advocacy part of ‘doing science?’

Many argue yes — advocacy, politics, and science are inseparable. Research is funded by taxpayers, with government agencies like the NIH and NSF deciding which scientific research efforts to support. Many believe that scientists should participate in advocacy, especially around topics that directly relate to their area of expertise. Having people who have devoted their lives to a topic weigh in on policy decisions certainly makes sense (they know a lot).

On the other hand, there’s a risk: if science is seen as “inherently political,” can it also be seen as objective? If objectivity is lost, the authority of science is diminished. When science and political advocacy are blended, “trust the science” begins to sound more like “trust my political views.”

When people are looking for scientific facts but get political advocacy instead, trust in science suffers. After the scientific journal Nature endorsed a candidate for president, those with opposing political views had reduced trust not only in the journal, but in scientists in general. As former NIH director Francis Collins said, “when you mix politics and science, you just get politics.”

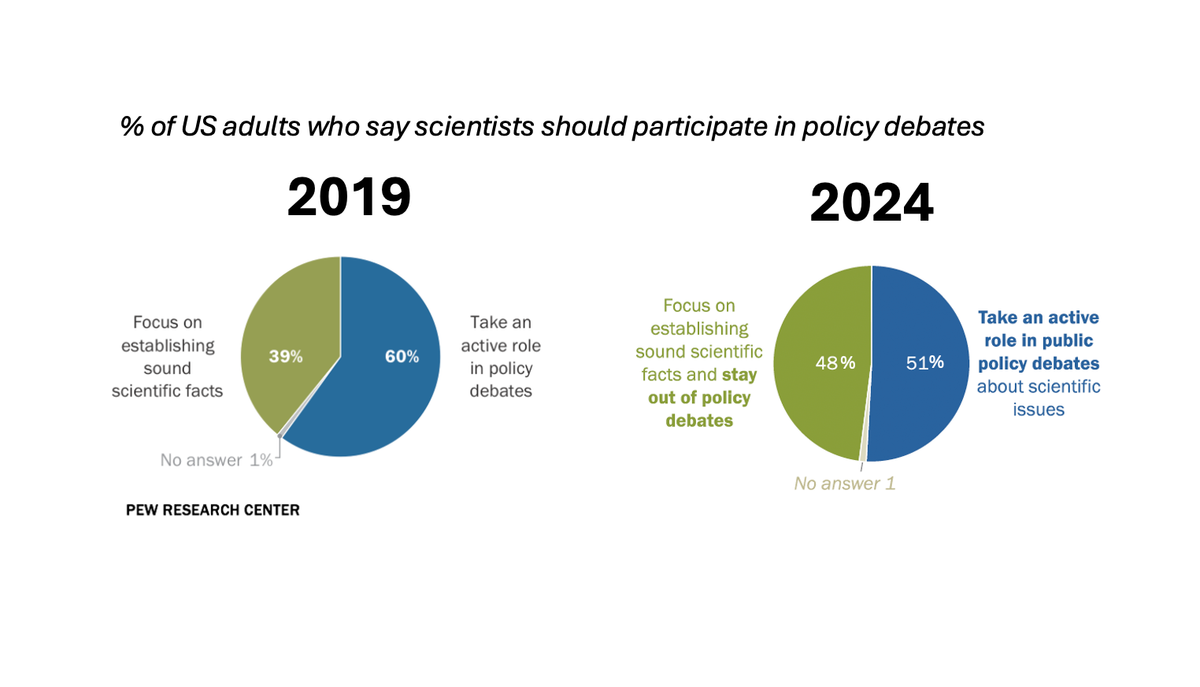

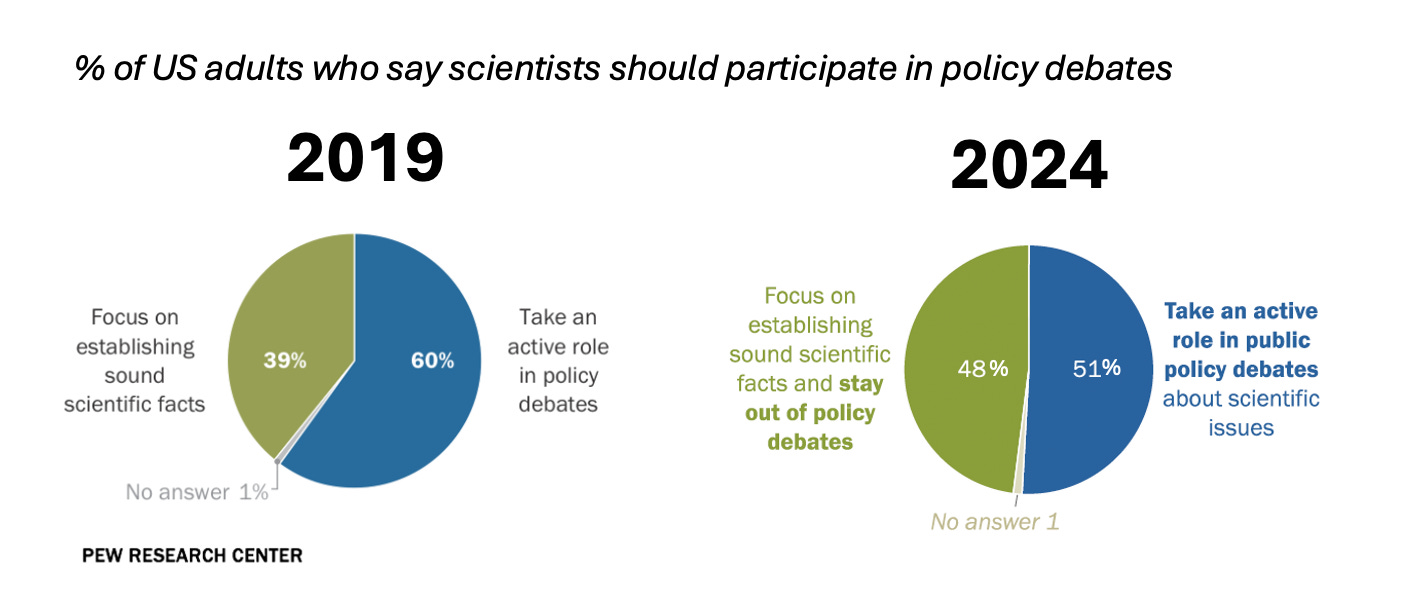

Where does the country stand? We’re split — nearly half of U.S. adults now say scientists should stick to the facts and stay out of policy debates—a share that’s grown since the pandemic.

Can we do both?

In my view, both advocacy and protecting the objectivity of science are essential. It is a fools errand to tell scientists they have to be silent on policy positions that are central to their work (or are making their work impossible). At the same time, blurring the lines between objective scientific fact and political advocacy has the potential to severely damage trust in both.

The solution? We need communication tools to do this better.

We need more words

Part of the challenge stems from the very word “science” — which has multiple meanings. It may refer to:

- The body of scientific knowledge, which includes decades of robustly established facts in addition to emerging data.

- The scientific method and scientific research, the messy but powerful process which produces objectively verifiable facts over time (but gets some things wrong in the process).

- The scientific infrastructure we have in place for doing research, including scientists, training programs, institutions, and funding mechanisms (including policy decisions that allocate funds).

- And sometimes, scientific policy is included in the broad definition of what “science” means — policy decisions on the environment, health, food, etc.

Scientific infrastructure and policy (#3 and #4) are to some degree inescapably political — research funding is decided by politicians (though historically has had consistent bipartisan support) and of course policy decisions involve politics.

But the scientific method and the knowledge it produces (#1 and #2) are different. They are objective — data doesn’t care how you voted, what your worldview is, or who is in office. Scientific experiments, when done well, produce as close to objective truth about the natural world as we can get.

And while scientists certainly have value systems and worldviews, the scientific method itself does not. Experiments might give the scientists answers that surprise or challenge their thinking. When done well, scientific results do not conform to our views, they shape them. The scientific method cannot even tell us what to do with scientific results — it can only tell us what outcomes to expect based on our choices.

The problem occurs when we blur the line and call it all “science”

‘Science says this is the right policy!’

Statements like this are where things get messy. Policy isn’t just about science — it involves cultural values, ethics, and priorities. Science can predict the outcomes of policy choices, but it can’t answer values and ethics questions or tell us which choice is “right.” Which is more important, life or liberty? That’s not a question the scientific method can answer.

Science-based advocacy is often a mix of objective data and subjective, personal values— and it’s easy to blur the line. When scientists advocate, they typically use their thorough understanding of the data and their own values and judgments about what’s best for their communities. That’s reasonable.

But not everyone in the community may share the same value system, even if they agree on the scientific facts. The mistake occurs when scientists treat their policy positions—with their personal values blended in—as if they carry the same authority as scientific fact: “Science says this is the right policy, and if you disagree, you’re anti-science!” This misrepresents what science is, and can significantly erode trust. Check out this post for an example of how this played out for COVID vaccine mandates.

So what do we do instead?

Advocacy is important, and protecting the objectivity of science is important too. Here’s how we can do both:

- Be clear what “science” means: Many people equate “science” with objective facts and the scientific method. If you’re talking about scientific infrastructure, funding or policy, make that distinction clear.

- Distinguish facts from values: Scientific facts are objective; our personal value systems are not. Both shape policy, but they shouldn’t be conflated as all representing “science.”

- Don’t equate policy disagreement with being ‘anti-science:’ People may agree on the data but still disagree with a policy for a reason totally unrelated to the science. Calling them “anti-science” is both inaccurate and unhelpful.

- Recognize the demand for “just the facts”: Many people want to understand scientific data without scientists’ personal values layered on top of them — there is a need for people who communicate science without venturing into policy debates.

So, is science inherently political? Some parts are, others are not. To advocate effectively without undermining trust in scientific objectivity, make it clear which “science” you’re talking about.

Kristen Panthagani, MD, PhD, is completing a combined emergency medicine residency and research fellowship focusing on health literacy and communication. In her free time, she is the creator of the medical blog You Can Know Things, available on Substack and youcanknowthings.com. You can also find her on Instagram and Threads. Views expressed belong to KP, not her employer.