Health institutions need to empower online creators, or risk getting left behind

It’s rare that an article has me nodding so much my neck hurts—but this one did. If you care about getting accurate health information to the public, I highly recommend you read it too.

Titled ‘For Expertise to Matter, Nonpartisan Institutions Need New Communication Strategies’ by Renée DiResta and Rachel Kleinfeld, it brilliantly explains a major change I’ve been noticing but couldn’t put into words so eloquently — the shift in how people are getting information and what counts as ‘trustworthy’ that is occurring in all aspects of society right now, and why experts and institutions are set up to fail in this new system (if they don’t adapt).

I highly recommend you read the whole thing, but here’s a quick breakdown and commentary on how I’m seeing this unfold in the world of health.

The old way: top-down communication

It used to be if you wanted to get a message out to the public, you couldn’t do it alone. You needed media outlets, newsrooms full of writers and editors, press releases from universities, and radios stations with a license to broadcast to disseminate your message. All of these forms of media have an editorial process, meaning messages were carefully considered, crafted and vetted before they were transmitted to the masses.

For decades, participation in this top-down media system signaled legitimacy. A doctor featured on the nightly news must know what they’re talking about, because they had to get through the vetting process of the editorial team. Polished and professionally-produced content were markers of credibility. A careful, measured tone was rewarded. And only a few messengers got their foot in the door — often those who had climbed the institutional ranks within their field and were deemed credible and important by the editors.

That’s not how it works anymore.

The new system: individuals and algorithms

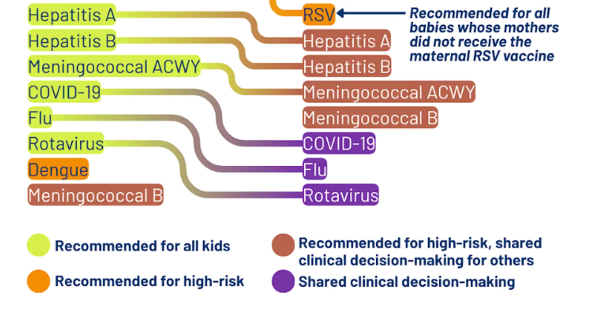

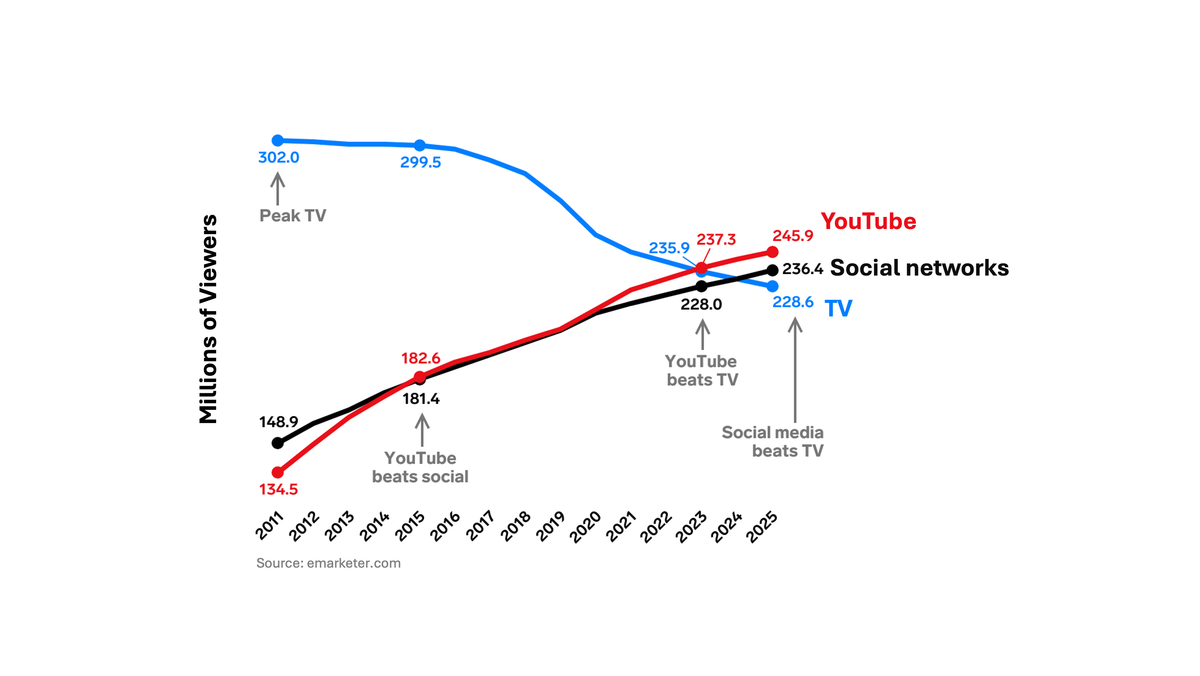

Now, that system is being drowned out by the online world. Social media dwarfs the reach of TV and legacy media outlets: major US broadcast networks like ABC and CBS get millions of views per day, YouTube gets billions. Popular Substacks, some authored by a single individual, now rival subscription metrics of major news outlets. Social media is now the top source for news (surpassing TV), and over half of adults use it to find health information. Some of this shift is likely financially driven — social media is (mostly) free, while a subscription to the New York Times is not. Legacy media still matters, but it is increasingly speaking to a smaller and smaller audience.

The top-down media system is no longer the most effective way to reach the masses. Learning to succeed on social media is now what’s required, because that’s where the people are. And the rules on social media are different — in many cases it rewards the opposite of what worked in the old system.

Institution-style communication is the exact opposite of what works online

While credentials, institutional approval, and a polished, professional tone used to signal credibility in the old media environment, for many it now signals the opposite. Carefully crafted institutional messages are treated with suspicion (‘are they really telling us the whole story? Whose controlling this behind the scenes?’) and a detached, impersonal tone invites distrust and boredom (‘are you just another a talking head?’)

Instead, social media rewards personality, storytelling, and emotion. In place of credentials and institutional approval, rawness and authenticity (being a ‘real person’) are now the markers of trustworthiness. Due to institutional failures, high profile scandals, and dwindling trust in institutions generally, people want to see beyond the polished exterior and know what you really think and what’s really going on. This is why unpolished videos in an informal setting like a mom driving in her car telling you her unfiltered opinion often resonate more than an institutional leader in a suit talking behind a podium. And with an algorithm full of viral content, messages that fail to entertain and engage fall flat. We do not expect warmth and silliness from a health pamphlet or press release, but we gravitate towards it on Instagram.

Academia sets us up for failure in this new media system

This shift is especially challenging for scientists, clinicians, and anyone else trained by academia, as the attributes that make people excel on social media are the exact opposite of how academia trains us to present ourselves. Academia teaches us to be polished, professional, and keep our personal lives (and personality) out of view. Communications training in medical school and graduate school is largely absent, and what is there emphasizes fancy graphs, citations, and a professional, emotionally detached presentation style. If you ask a scientist to create an Instagram post, they’ll often create a tiny PowerPoint slide. If you ask a doctor to make a reel or YouTube video, they’ll often create a mini lecture fit for a medical school classroom.

In the competitive attention environment of social media, the academic style simply doesn’t work. The absence of personality, storytelling, emotion, and rawness makes it less engaging, and the algorithm will learn this and stop showing it to people. Academics and institutions have a lot of important things to say, but their message will reach fewer and fewer people if they fail to adapt their communication style.

How do we adapt?

I won’t claim to have mastered every secret to success in the online world, but here’s a few tips from DiResta and Kleinfeld’s article along with a few tips of mine to get started:

- Be a real person. People want to know you’re a real human being like them, not a talking head delivering a scripted message. Show your flaws, concerns, and genuine emotions. Have a conversation rather than delivering a crafted lecture. Talk about your dogs (or bring them on camera with you.) It may seem trivial, but simply relaxing and being the human you actually are instead of the impersonal academic many of us were trained to be can make a big difference.

- Bidirectional engagement, not just talking at the audience. The most successful creators develop trust with their audience through engagement — it’s not just a one way lecture, but a conversation with a community through comments, stories, and listening to and integrating feedback from the community of followers.

- Show up in advance. Building an audience online takes time, and trusted messengers are trusted because they put in the work ahead of time. If the plan is to show up online only in an emergency, people are less likely to listen to what you have to say.

- Learn some basics about the algorithm. Social media algorithms are to some degree a black box, but there are some rules that apply across most platforms. Links are often penalized, don’t put them in the main post. Reels are judged by their watch rate of the first few seconds, make sure those 3 seconds aren’t waisted clearing your throat. Comments drive engagement, including your responses. Your message needs to be tailored to the platform, not an announcement that information exists somewhere else. Taking the time to learn a few basics can make a big difference.

- Show the individuals behind the institutions. Individuals have a distinct advantage over institutions on social media because they are humans. Institutions can excel in this new environment by supporting individual creators who already work for them and by growing communications teams that show the faces behind the organization in a relatable, informal, authentic setting (such as a ‘day in my life’ video, not a university photo and bio line.)

- Sometimes unpolished is better. As someone who loves graphic design this drives me a little crazy, but sometimes unpolished screenshots do better than beautiful infographics, and informal sketches may resonate more than professional animation. This principle isn’t universally true — good lighting and good audio certainly matter, but the more authentic and personal it feels — that a real person took the time to draw, write, or explain something to you, the better.

- Collaborate. Collaborations between creators can help both reach new audiences. For institutions that find this kind of outreach daunting, partnering with established creators is another option to pursue (like the New England Journal of Medicine collaborating with beloved internet comedian Dr. Glaucomflecken to teach us the latest medical literature).

- Support creators. Most creators volunteer their nights and weekends to make content, often with little (or zero) financial compensation. Institutional support varies from outright discouraging students and staff from using social media to tolerating it but not providing any time or funding to support it. This model has to change if we want expertise to be understood and valued.

Institutions and experts must adapt or their influence will continue to dwindle

“In this ecosystem, influence belongs not to those who speak most precisely or factually but to those who understand where—and how—audiences are listening.”

Institutions are needed. At a core level, they are what is created when humans organize and work together to solve problems, which is a very good thing. Knowledge is not always easy to come by, and we need people and systems devoted to doing the careful, slow work of systematically studying reality so we can uncover what is real and true. Social media doesn’t reward that, nor will it do it for us.

But if those doing the slow, careful work don’t figure out how to get their message across to the public, that knowledge will stay hidden, as will the value of the work itself. That is what we are seeing happen in real time right now. Communication to the public has fundamentally changed, and experts and institutions must adapt, recognizing that trust and credibility are no longer earned by titles and letters after our names, but by showing up and meeting people where they are listening.

Coming up on Substack Live: I’ll be joined next week by Matt Lanza —meteorologist, weather communicator, and author of the beloved weather blogs Space City Weather and The Eyewall. Matt and I have been internet friends since the pandemic and we’ll talk about the surprisingly similar challenges we face in public health and weather communication and how we can adapt to this new media environment. We’ll be live Thursday October 30 at 1 pm ET. Hope you’ll tune in and join the conversation!

Kristen Panthagani, MD, PhD, is completing a combined emergency medicine residency and research fellowship focusing on health literacy and communication. In her free time, she is the creator of the medical blog You Can Know Things, available on Substack and youcanknowthings.com. You can also find her on Instagram and Threads. Views expressed belong to KP, not her employer.