Words that confuse people: vaccine schedule edition

Vaccine requirements, vaccine recommendations, and "shared decision-making"

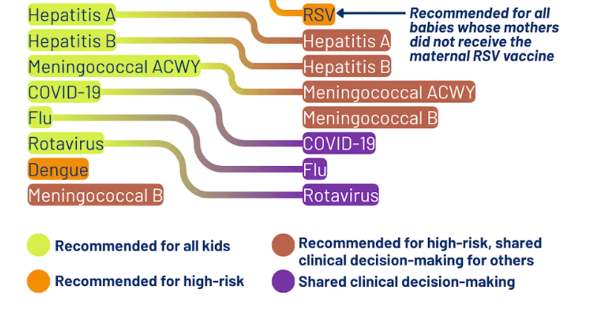

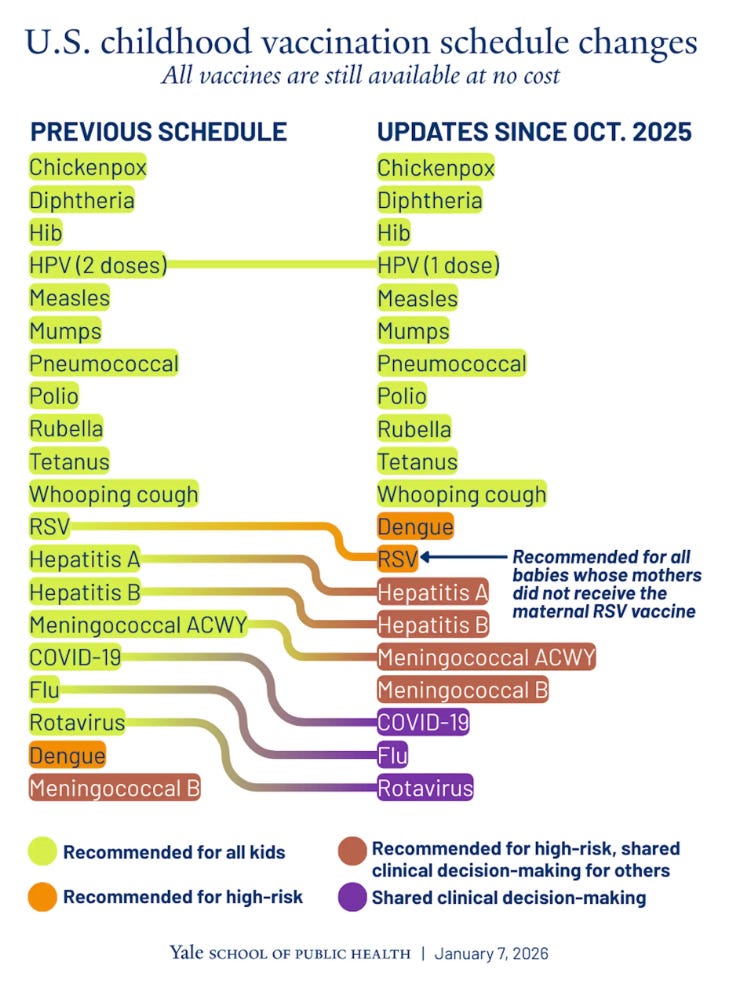

Last week RFK Jr’s HHS announced a change to the childhood vaccine schedule in attempt to more closely align it with Denmark. Several of the vaccines including those for influenza and rotavirus were changed from “recommended” to “shared decision-making.”

The phrase “shared decision-making” has been used a lot this past year, and comes laden with ambiguity as to what it actually means. If physicians say we don’t want shared-decision making for vaccines, does that mean we want to force decisions on parents? Of course not, but the ambiguity makes it easy to misinterpret (and weaponize) this phrase.

So let’s break it down — what is “shared-decision making,” and how is it different from a “vaccine recommendation” or a “vaccine requirement?”

“Shared-decision making” can mean different things in different contexts

Definition A (colloquial definition): The patient (or parent) is involved in decision-making.

If we take the phrase at face value, medical decisions already involve shared decision-making. Ultimately, every medical decision is the patient (or parent’s) call, and it’s up to them to decide if they want to accept physician recommendations.

For example, if a patient needs a blood transfusion, the physician 1. recommends it, 2. explains to the patient why it’s needed, 3. explains the risks, 4. answers questions, and 5. obtains the patient’s consent before proceeding. As long as the patient has mental capacity to make decisions, they can decline the blood transfusion if they would like to. Using the colloquial definition, you could call this “shared decision-making” — the physician and patient are both involved in the decision-making process. (There is an exception for patients who don’t have mental capacity to make decisions like those with severe dementia or children, in which case a family member/parent is consulted instead.)

If we use this definition, all vaccines on the childhood vaccine schedule have always involved “shared decision-making” — the physicians and parents discuss them, and the parents make a decision about vaccination.

But in the medical world, “shared decision-making” has come to mean something a little more specific.

Definition B (medical definition): A collaborative discussion of pros and cons when there isn’t one clear recommended treatment.

In medicine, when we say “shared-decision making,” we’re referring to something more specific than “the patient is going to be involved in the decision.” This phrase is typically reserved for situations where the evidence doesn’t give one clear recommendation, and we have multiple treatment options to choose from. In these scenarios, the physician talks through the pros and cons of the available options with the patient, and a decision is made collaboratively.

If a patient has a dangerously low hemoglobin level and the physician recommends a blood transfusion, talks through the risks and benefits, and the patient ultimately makes a decision, this typically would not be referred to as “shared-decision making” because there was one clear evidence-based treatment option (a blood transfusion) — even though the patient was obviously involved in the decision.

When the medical evidence provides a clear recommendation for treatment, the phrase “shared-decision making” is often not used, even though the patient is still very much involved in the decision.

You can see how this ambiguity makes things confusing. If a physician pushes back against “shared decision-making” for vaccines on the childhood vaccine schedule, they’re not pushing back against Definition A (parents should be involved in decisions), they’re pushing back against Definition B (the implication that no clear recommendation exists).

Shared decision-making was never supposed to replace evidence-based recommendations

Vaccine recommendations are just that — recommendations. The childhood vaccine schedule is a series of recommendations created by teams of scientists who study population data to evaluate which vaccines provide significantly more benefits than risks, and for whom. It’s not recommended that newborns get the MMR vaccine, but it is recommended for children at 12 months (sometimes earlier in higher risk situations).

Changing vaccine “recommendations” to “shared-decision making” falsely implies there is no clear evidence-based recommendation, and it shifts a large burden onto individual parents and pediatricians. Instead of relying on the work that has already been done to determine which vaccines are beneficial for which children, it asks each parent and pediatrician to redo this work for every child. Some parents may welcome this as they want to do this work on their own, but many others will find it confusing and overwhelming. (And for those who do want to do this work, they already had the option to do so before recommendations were replaced with “shared decision-making.")

Vaccine recommendations are a part of division of labor for society — we figured out long ago it makes sense for us to divide up work so we’re not all trying to do everything on our own. Reviewing the population level data to determine the risk/benefit ratio for each vaccine requires a lot of work, and it’s helpful to rely on people who have devoted their lives to the topic instead of asking each pediatrician and parent to do the work individually.

Vaccine recommendations aren’t mandates

And finally, let’s distinguish vaccine recommendations from requirements. The childhood vaccine schedule has always provided recommendations, not requirements — there is no universally required vaccine in the United States.

Immunization requirements come from specific locations — particularly locations that involve children coming together and sharing germs like schools, daycares, some pediatrician offices. Recognizing that vaccines reduce the spread of infections to other people who may be at risk, vaccine requirements are implemented in specific locations to protect people in attendance who are at higher risk (younger children who can’t be vaccinated yet, immunocompromised children, etc.)

“Shared decision-making” sounds like empowerment, but will likely lead to confusion

The discussion around “shared decision-making” isn’t about whether parents should have a say in medical decisions — they always have and will be the decision-maker for their child’s health. It’s about whether we clearly communicate when the medical evidence points to a strong, population-level benefit versus when the evidence is truly ambiguous. The shift in language on the vaccine schedule communicates uncertainty where we previously had clarity, and it shifts the burden of interpreting complex population data onto individual parents—many of whom want clear, trustworthy guidance, but are now offered confusion.

Kristen Panthagani, MD, PhD, is completing a combined emergency medicine residency and research fellowship focusing on health literacy and communication. In her free time, she is the creator of the medical blog You Can Know Things, available on Substack and youcanknowthings.com. You can also find her on Instagram and Threads. Views expressed belong to KP, not her employer.

Thanks to David Higgins, MD, MPH for his feedback on this post, I highly recommend you subscribe to his newsletter Community Immunity if you haven’t already!