Why I stopped using the word 'misinformation'

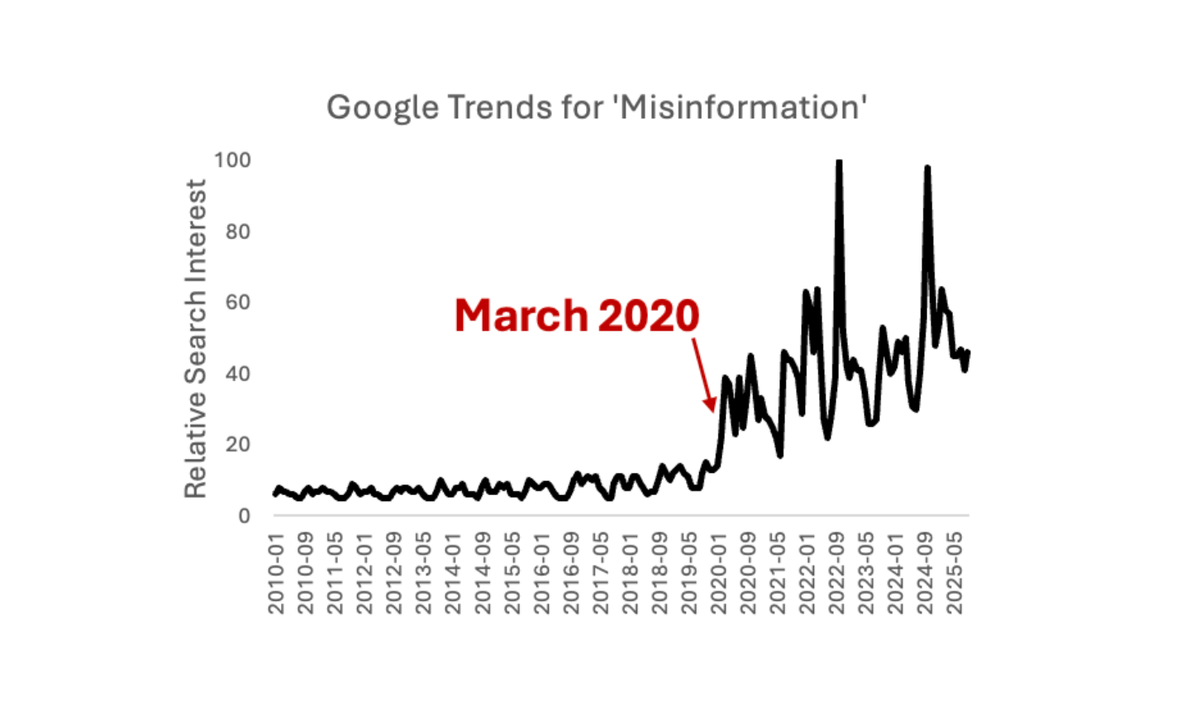

The word ‘misinformation’ entered my regular vocabulary around the time it did for much of the country — March 2020. Discovering my newfound love for explaining science and addressing COVID rumors online, that seemed to be the logical term to use. “Misinformation alert!” “Fact check!” “This has been debunked!” became common phrases in my writing.

Several months into my novice career as a science communicator, I got the most useful communications feedback of the entire pandemic. Someone close to me sent me a text: “hey Kristen — your content is great. People need it. But it would help if you stopped using the word ‘misinformation.’ That turns a lot of people off, and they’ll stop listening to you.’

I’ll confess, I was surprised. I was in my own science communication bubble and everyone I looked up to online was using that term. It is the accepted academic term, after all.

But I trusted the person who texted me to help me see outside of my academic echo chamber, and I took their advice. It turns out for a lot of people (often the very people I was trying to reach), that word immediately causes them to bristle. ‘Know your audience’ is communication 101, and I decided it didn’t make sense to use a word that causes a negative reaction for my intended audience. So I found other synonyms to use — rumor, falsehood, inaccurate information, or this isn’t true, here’s why.

Why ‘misinformation’ gets under people’s skin

‘Misinformation’ has become a polarizing term, for many reasons. For some, the negative connotation was the result of shame-based scientific messaging, and misinformation started to feel like a slap in the face — like their words and questions were being slapped down and snuffed out. It carried a sting with it: ‘You’re spreading misinformation! Shame on you!’ To others, the word means “what they want you to believe but won’t let you question” or “the establishment view,” and immediately sows distrust. During the pandemic, genuine questions that required scientific nuance were mixed in with blatant falsehoods, and the word “misinformation” was applied to it all, often with a tone of condescension and disgust. It makes science seem black or white (it’s either misinformation or it isn’t), when a lot of scientific questions during the pandemic were in a messier gray area of emerging data.

Whether these are ‘correct’ interpretations of the word really doesn’t matter anymore — that is how many people interpret it. Once a word loses a shared understanding of its meaning — one group believes it means “inaccurate information” and another interprets it as “information you’re not allowed to question” — it stops serving its purpose as an effective tool for communication.

I recently participated in a discussion with Make America Healthy Again supporters on Brinda Adhikari’s podcast Why Should I Trust You, and one of the participants called out this issue directly. We were discussing bias in media, disclosing bias, and why we trust the news sources we do, and this is what Jacqueline Capriotti, a mom of two adult children with cystic fibrosis and MAHA supporter, said (slight edit for clarity):

“They'll [news organizations] use terms that do disclose their bias, but they're not doing it in a way that they think that they're openly disclosing their bias. So I'll give you an example, like terms like 'anti-vaxxer,' 'misinformation,' 'conspiratorial,' 'anti-science.' When I see these type of terms in an article that is coming up as news, you have taken a class of individuals or a group of individuals or an individual and ‘othered’ them already. So you've put them in a classification and you've completely ‘othered’ them and you've imposed this predetermined title on them by giving them these type of terms.”

After the podcast, I asked Jacqueline if it’s fair to say that articles that use ‘misinformation’ would feel less trustworthy to her. She said yes, and explained why (emphasis mine):

“When writers or institutions throw around terms like misinformation, disinformation, conspiracy theorist, anti-science, or misinformation spreader, it lands as deeply negative. It doesn’t just challenge an idea; it shuts down a conversation. As I mentioned in the podcast, it “others” individuals or whole groups. It tells readers: these people are not worth listening to. And in that moment, you’ve lost both the person who might have asked an honest question and the readers who may identify with them.

To me, it feels like a slap across the eyes, mouth, and ears — see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil. Labeling becomes a shortcut to dismissing. That is not the same thing as correcting information. By all means, correct something that’s factually wrong. Present better data. Offer a stronger interpretation. But when you label the source itself with a prepositioned title — anti-vaxxer, conspiracy theorist, misinformation spreader — you’ve stepped out of dialogue and into silencing.

I’ve been encouraged time and again by my family’s medical teams that there are no stupid questions. That lesson has carried us through the most complex, rare, and devastating medical challenges. When you make someone feel stupid — or worse, an enemy — for asking a question, you minimize their worth and their value. And you discourage the very thing we need more of: questions. Because more questions lead to better answers.”

Do I have to stop using ‘misinformation’?

That is entirely up to you, of course. Whether it is a helpful word depends on what your goal is and who you are trying to communicate to.

In academic circles, it’s still the accepted term, and I regularly use it there. If you’re writing an academic paper, go ahead.

But if your goal is to “address misinformation” — usually misinformation is not a helpful word to use. Often many people who would benefit from your explanation will be turned off if you start by labeling something as misinformation. And that’s not a very effective way to communicate — by using words that trigger distrust.

Kristen Panthagani, MD, PhD, is completing a combined emergency medicine residency and research fellowship focusing on health literacy and communication. In her free time, she is the creator of the newsletter You Can Know Things, available on Substack and youcanknowthings.com. You can also find her on Instagram and Threads. Views expressed belong to KP, not her employer.