Hot takes and cold fronts: public health and weather comms in the new era

Yesterday I had the pleasure of chatting with my friend Matt Lanza (meteorologist and author of Space City Weather, The Eyewall, and Lanza's Stanzas) about the shift to new media that’s unfolding in the world of weather and public health (and everywhere else). Even though we are in completely different fields, the communication changes and challenges we’re seeing are surprisingly similar.

Matt and I are thinking of doing more chats like these — feel free to comment or email us about what was helpful and ideas for future chats!

Borrowing an idea from Jeremy Faust who first introduced me to Substack Live, below is an AI-generated summary of our conversation if you don’t have time to watch the whole video.

Introductions

Kristen introduces herself as a fourth-year emergency medicine resident at Yale, part of the Yale Emergency Scholars Program, and the author of the newsletter You Can Know Things. She explains her writing shifted from COVID myths to general public health, with a recent focus on effective communication strategies. This is the focus of their interdisciplinary discussion.

Matt introduces himself as a meteorologist in Houston. He expresses admiration for Kristen’s ability to communicate complex public health topics. He posits that their fields face similar problems as scientists, dealing with misinterpretation and reaching different audiences. He references a Carnegie Endowment discussion and an article by Renee DiResta and Rachel Kleinfeld about the need for nonpartisan experts to adopt new communication strategies as the world has changed due to social media misinformation.

Decline of Old Media and the New Media Style

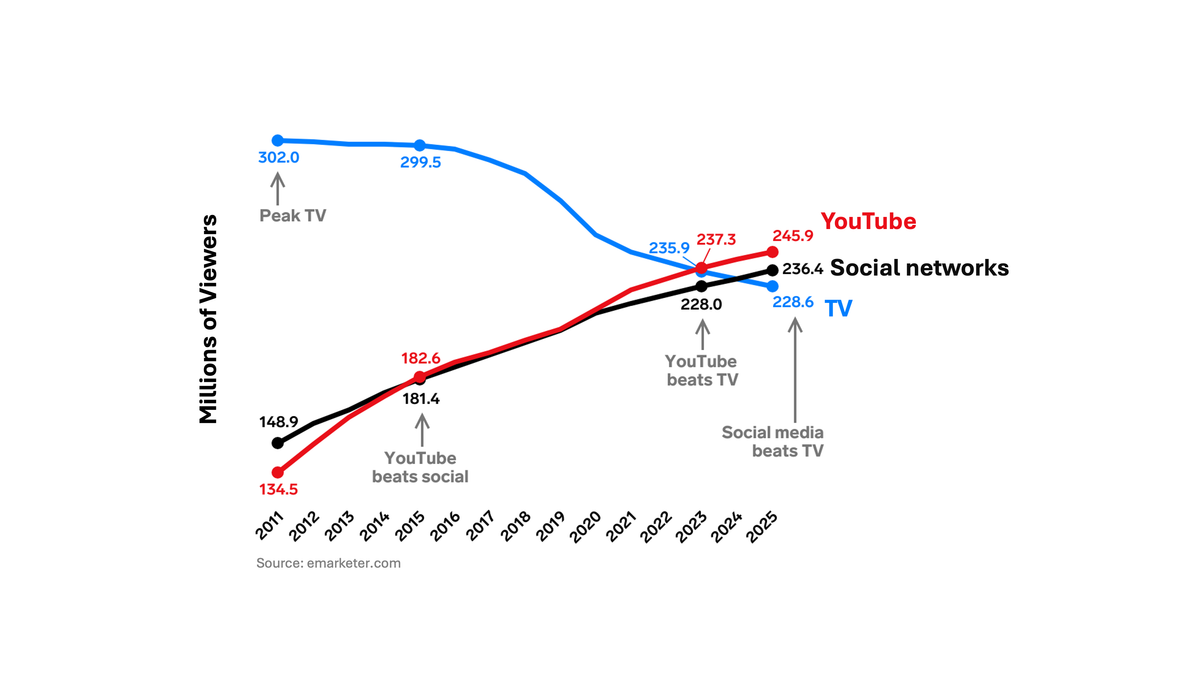

Kristen plugs Matt’s highly regarded Houston weather blog, Space City Weather, and his new Gulf hurricane focus, The Eyewall. She then dives into the key takeaway from DiResta and Kleinfeld’s article: the top-down, legacy media system is losing impact, and communication on social media is critical for institutions and experts to reach audiences. The traditional, polished, impersonal style of expert communication is the “exact opposite” of what works online.

Kristen elaborates on what doesn’t work (the “talking suit” with no personality) versus what people gravitate towards: emotion, rawness, and authenticity. She gives a specific example: on Instagram, less-polished, “handmade” content (like a screenshot of a post) often performs better than her carefully designed Adobe Illustrator infographics, suggesting that authenticity now trumps graphic polish. She concludes that institutions must learn to navigate this new system effectively.

Humility, Avoiding Condescension, Writing How You Talk

Matt agrees, noting that while there’s a desire for expertise, it’s about how it’s presented. The old way was rigid and “stodgy.” Experts must present information that is understandable and doesn’t come off as condescending. He shares his own realization after graduating college that simply being a scientist wasn’t enough; he needed to write and talk to people, avoiding jargon or always explaining it.

Kristen discusses the tension over the term ‘expert.’ She notes that the old assumption—that people should believe you purely because you have an MD or PhD—no longer works. The way forward requires knowledge, but also approaching communication with humility and a genuine desire to teach, not with an attitude of “I have the PhD, so I know what I’m talking about.”

Failure of Traditional Media, Success of Hype-Free Communication, and Storytelling

Kristen recounts her experience during Hurricane Harvey (2017). She felt the Weather Channel and “old media” failed Houston by over-hyping and not communicating uncertainty well. In contrast, Space City Weather was essential, providing timely, hype-free updates every six hours with the goal of calming people down and clearly communicating necessary actions. She credits this approach—not chasing clicks, but focusing on clear, humanized, timely updates—as what’s needed in both weather and public health.

Matt confirms their approach was to be the antithesis of the current media landscape by being “hype-free” and even “boring most of the time,” which buys them credibility when things get serious. He warns against the “business of media” where engagement leads some meteorologists to post “crazy maps” with benign explanations, leading to the “cry wolf syndrome.” If “everything’s an emergency, then nothing’s an emergency.”

Matt highlights Kristen’s tactic of framing intense political/public health topics (like a contentious hearing) by cutting to her dog and saying, “Whoa, whoa, whoa, let’s slow down. Here’s my dog.” He praises this as a great way to instantly calm people down and make the complicated topic relatable. Kristen agrees, noting that she now purposely introduces a storytelling element to prevent her communication from sounding like a lecture.

Matt addresses the misconception that this type of ‘new media’ communication is only for “younger people.” He argues that any expert can do it, regardless of age; it’s about being willing to understand that the world has changed and dedicating the time. Kristen agrees, stating they need the knowledge of experts with 20-40 years of experience, but these experts need to be willing to adapt to the new media environment.

Gatekeeping in Science Communication

Matt identifies the core issue as the democratization of weather data, which has been freely accessible for over 15 years. This has allowed a mix of people—some well-versed, others “engagement farming”—to post maps and explainers. The challenge is dealing with the noise and hype from these non-meteorologists.

Matt comments on the rise of YouTubers (e.g., Ryan Hall, Max Velocity) who do multi-hour live streams during severe weather. They are “very relatable” and garner huge views, even if their technical explanations aren’t always perfect.

These streamers are taking market share from traditional outlets (like The Weather Channel) because they are interesting, exciting, and relatable. The old model of TV cut-ins is losing relevance. Matt concludes that the consumer will benefit, but notes that the streaming field lacks diversity, being mostly “younger white dudes.”

Kristen notes a similar tension in science: the best communicators often lack the highest credentials. She places herself in the school of thought that recognizes there aren’t enough niche experts with both the skills and time to communicate. She argues against gatekeeping, saying that if communicators are generally accurate but don’t have all the right credentials, more senior experts should help them out rather than “bash them” for minor technical errors.

Kristen shares her own initial guilt about starting her blog as a PhD student without credentials, but realized the government’s communication wasn’t “cutting it.” She stresses the need to embrace talented communicators and give them training, rather than shutting them down for lack of formal status.

Matt discusses a National Weather Association panel that included YouTubers, intending to show meteorologists that the streamers’ methods are working. He advocates for ending gatekeeping and being more inclusive, even with “somewhat inexperienced” people, to ensure the public receives information. He argues that the world has changed, and not everyone watches TV anymore.

Kristen asserts that only two things matter online: accuracy and understandability. The traditional checkpoints of credentials and institutional approval “just doesn’t really matter anymore online” and shouldn’t, as it stifles talented individuals.

Kristen recounts a social media “science communication war” over a student’s advice on how a non-expert should start reading a research paper (skip the methods first). She felt the student was unfairly bashed by senior scientists for a perceived “mistake.” Matt agrees, sharing his own struggle with advanced calculus in college to stress that it’s important not to discourage students by overwhelming them, confirming the student’s advice was sound for a general audience.

Funding Cuts and Government Infrastructure

Kristen asks Matt about the impact of destabilizing funding cuts and staff firings/buyouts in the weather world and how the new style of communication can help fill the gap created by a shrinking government infrastructure.

Matt calls the loss of experienced National Weather Service staff “tragic” because of the loss of mentorship for the remaining capable team. The bigger threat was the proposed cut to research funding, which would stifle advances. He highlights that Congress thankfully restored much of the NOAA funding because policymakers understand the value of weather services to local emergency managers. He gives the example of Hurricane Melissa forecasting, which relied on years of federally-funded research, even for new private models like Google’s DeepMind.

Kristen agrees that the difficulty lies in communicating the tangible value of infrastructure and preparedness before a disaster strikes. She states that the same issue exists in public health with pandemic preparedness: the loss of infrastructure is only truly felt when the next pandemic emerges.

Restoring Trust and Credibility After the Pandemic

Responding to an audience question about restoring science/medical credibility after COVID, Kristen states there is no simple answer and it varies by audience. She identifies echo chambers as Problem #1: communicators primarily reach people who already trust them. The solution is encouraging more diverse communicators from different backgrounds who can speak the “native language” of cultural bubbles with lower trust.

The second step is admitting where things went wrong, ideally on a national scale. She notes that many communicators she knows acknowledge genuine mistakes were made. Publicly acknowledging mistakes and showing a lack of rigidity is essential for trust building.

Kristen discusses her work looking back at the pandemic, explaining where communication “went sideways” and was misinterpreted, arguing that many public health communicators didn’t see how their messages were landing. She suggests that if people could have good faith conversations about contentious issues (like vaccine mandates), people might realize the “other side” was coming from a genuine place of concern, even if they don’t agree on the ultimate decision.

Kristen gives a shout-out to the Why Should I Trust You? podcast for modeling this, emphasizing the goal is to hear each other’s perspectives and realize the vast majority want “what’s best for our communities.” Matt agrees, noting parallels in meteorology, especially with climate science, which is often a “contentious, politically charged debate.”

Climate Change and The Importance of Nuance

Matt argues that over-attributing extreme events (like Hurricane Melissa) solely to climate change politicizes the issue and causes people to “tune you right out.” He clarifies that warming water likely made Melissa more likely/intense but didn’t cause it. He stresses that problems like flooding are complex and multi-dimensional (e.g., land subsidence, over-development, population explosion), not just caused by one issue.

Matt says it’s up to scientists to explain these complex problems well. He notes that by focusing solely on one issue (like climate change), scientists sometimes lose sight of the bigger picture, causing people to tune out.

Kristen calls this the central trade-off of science communication: balancing the need for simplicity to communicate the message against nuance for accuracy. She cites data suggesting that people can handle and appreciate nuance, and it actually makes the messenger more trustworthy, but acknowledges the challenge of getting people’s attention long enough to communicate it.

Matt mentions a draft post titled “The Death of Nuance” and believes the world needs nuance desperately but doesn’t have time for it. He advises communicators to “Lead at the beginning” with the main takeaway, then get into the nuance. He pushes back against the idea that the public is “dumb,” saying people are smart and have the ability to comprehend complex things. “Don’t let perfect be the enemy of good.”

Kristen asks Matt an audience question: Is there an increase in severe weather frequency due to climate change? Matt gives a nuanced answer: Flooding and heat waves are more connected, hurricanes may be less frequent but more intense, and the research is “mixed” for others like tornadoes. He concludes that a warmer Gulf likely makes for a more hospitable severe weather environment in the Plains, but “there’s a lot that we still have to learn.”

Wrap Up

Kristen praises Matt’s “beautifully nuanced answer” and wraps up the discussion, noting they are at the one-hour mark. They thank each other for the conversation and share Matt’s newsletter information (Space City Weather and The Eyewall).

Kristen Panthagani, MD, PhD, is completing a combined emergency medicine residency and research fellowship focusing on health literacy and communication. In her free time, she is the creator of the medical blog You Can Know Things, available on Substack and youcanknowthings.com. You can also find her on Instagram and Threads. Views expressed belong to KP, not her employer.