Faith, Facts, and Trust

What faith has to do with trust in science, and what we can do about it

Last week I got to participate in an incredibly unique event: The Evidence Collective brought together scientists and doctors with what may seem like unlikely partners: pastors, priests, and faith leaders.

We spent a day talking — not only finding overlap in our missions (turns out we are all fundamentally motivated by the same thing: caring for people who are hurting), but also dissecting the ways the alleged “faith-science” gap has damaged trust in both.

Are faith and science actually incompatible?

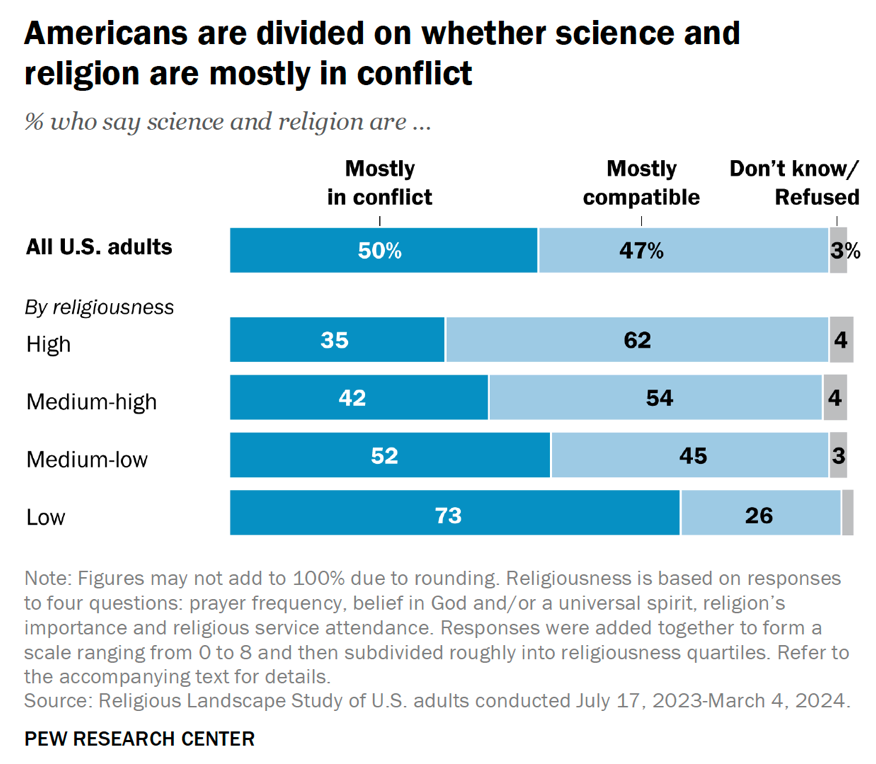

One theme that emerged over and over again is the idea that faith and science are in conflict, and that people must pick one or the other. (And that those who pick faith are viewed as less intelligent for it.) A recent Pew survey backed this up, revealing about half of Americans believe science and religion are “mostly in conflict.” Of course, there are some specific religious beliefs that clearly conflict with scientific consensus, but this survey reveals something broader — a widespread belief that religion is mostly at odds with science.

If this is actually true, it’s a big problem for trust in science. About two thirds of the US population identify as religious. “Trust the science… (which btw, is incompatible with your silly faith)” is not a winning message.

Where is this narrative coming from?

Growing up, I remember this faith-science conflict seemed to be in the air. As a Christian and a student who absolutely loved science, I got it from both sides. I was vaguely warned at youth group that certain scientific topics (like evolution) — and even college generally — could make me lose my faith, and to be very cautious. From the science side, a research mentor told me the same thing… that eventually I’d “grow out of” my silly beliefs as I became more educated, a sentiment echoed in snide comments from my science professors. I entered college with this foreboding impression that eventually I would have to choose between science and spirituality; I couldn’t have both.

But I loved science, so I persisted. I majored in Chemistry with a focus on biochemistry, and took genetics, cell biology, organic chemistry, philosophy, logic, among a myriad of other courses. I kept looking for this “fundamental conflict” between faith and science that I had been told about, and I couldn’t find one. To be sure, there were some very specific religious beliefs that were incompatible with science (such as the belief that the earth is 6000 years old). But no matter how many science classes I took, I failed to discover anything core to my faith that had been disproven by the scientific method. And I learned that wasn’t even science’s job — the scientific method studies physical, reproducible natural phenomena, and simply can’t answer most questions about faith, spirituality, morality, and purpose. Not giving an answer is certainly not the same as disproving something.

But this perceived conflict seemed so strong, surely I was mistaken somewhere? I must confess, it was a bit of an existential crisis. I tried to talk to my science professors, but didn’t get much help (and more often got dismissed). And no one at my church was a scientist I could talk to.

Finally, I found Francis Collins’ book The Language of God. Reading the book itself was impactful, but perhaps the most important thing for my young college self was to learn that the director the NIH (who had an MD and a PhD!) was a person of faith. If faith really was a sign of an irrational, unscientific mind, strange that a person like that was in charge of our nation’s leading biomedical research institute. Reading Dr. Collins book gave me permission to do both — I could become a scientist (ultimately getting an MD and PhD myself), and keep my faith. Turns out I didn’t have to choose.

How this narrative has impacted trust in science

For me, the faith-science conflict narrative came from both sides, but it was louder from the science side. The Pew survey supports this: those who are less religious are most likely to perceive a conflict between science and religion, while religious folks were more likely to view science as compatible with their faith.

Other research backs this up. A recent study found that people who are not religious are more likely to believe that faith and science are incompatible, leading to a perception that Christians are less intelligent or scientifically minded. Another study looked at what this bias does: when Christians were told that faith and science are incompatible, their performance on a scientific reasoning task got worse — an effect that was largest among Christians who strongly identified with science (like me). Said another way, perpetuating the stereotype that people of faith aren’t scientifically minded can become a self-fulfilling prophecy — potentially pushing these groups out of science altogether.

Shared faith background can increase trust in public health measures

What does this all have to do with trust in public health? There’s the obvious part: a general perception that “scientists think I’m stupid because I believe in God” certainly doesn’t help build trust in the science underlying public health measures.

But it’s more than that: we know that trust isn’t just about facts, but it is also about the messenger — and shared faith matters, a lot.

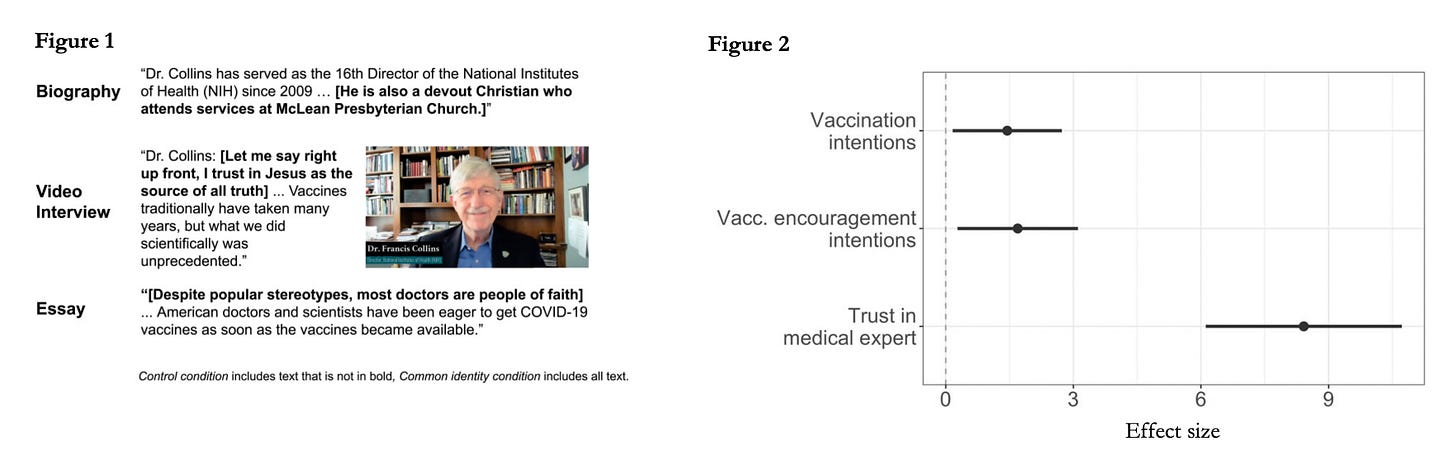

A pandemic-era study measured this: American Christians who were unvaccinated watched a video of Francis Collins answering questions about COVID vaccines. Half of the participants learned Dr. Collins is a devout Christian and heard him talk about his faith; the other half didn’t. The information about vaccines was identical.

The study found that simply knowing that Dr. Collins shared their faith increased trust in him — and increased their intention to get vaccinated and encourage others to vaccinate as well. The facts didn’t change. The messenger didn’t change. Only the shared faith did.

We need more trusted messengers like Dr. Collins who can connect with the faith communities who raised them. But sadly, the “religious people are unscientific” stereotype makes this hard to do. Not only does it discourage young students of faith from pursuing science, but for those who do become scientists or doctors, it makes it harder to be public about their faith due perceived backlash and judgement from their peers.

Where do we go from here?

Rebuilding trust in science doesn’t happen through data alone — it requires recognizing where and why trust is breaking down, and finding the bridge-builders who can restore it. Here’s a few steps we can do going forward:

- Avoid reinforcing a false choice. While the perception that science and faith are incompatible is widespread, this stems in large part from a misunderstanding of what kind of questions science can answer. Science has disproven some specific religious claims, but this does not mean faith and science are incompatible generally.

- Resist the stereotype. The idea that religious people are less intelligent or less scientific can quietly discourage students who might otherwise thrive in science. We need these students, and rejecting this stereotype can help make them feel welcome.

- Remember that trust is relational. Facts matter, but so do shared values and identity. Partnering with faith leaders and supporting scientists who can authentically engage their own faith communities can make a real difference.

- Make space for bridge-builders. Many clinicians and researchers hesitate to be open about their religious beliefs for fear of judgement from their peers. If we want bridges, we have to make it safer to build them.

Kristen Panthagani, MD, PhD, is completing a combined emergency medicine residency and research fellowship focusing on health literacy and communication. In her free time, she is the creator of the medical blog You Can Know Things, available on Substack and youcanknowthings.com. You can also find her on Instagram and Threads. Views expressed belong to KP, not her employer.